Despite Canada’s vaunted medical “safety net”, our hospital system is not very safe, and injured patients seeking redress face a years-long battle with little chance of winning. On top of that, plaintiffs – as taxpayers – often pay the defendant’s bill.

Canada’s patient safety performance is below the OECD average of 37 developed countries. Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) 2019 data shows Canada’s overall performance aligns with the international average for 32 out of 57 health indicators, but we are below average on 12 indicators and above average on only 13. Tracy Johnson, a Director at CIHI, says, “We are lagging behind OECD countries in areas of patient safety. These are serious issues that are often preventable, and improving our performance in these areas will result in safer care for patients.”

- Obstetrical trauma rates (tears during vaginal childbirth) are twice the OECD average, and are not improving.

- Rates of avoidable complications after surgery, such as lung clots after hip or knee surgery, are 90% higher than the OECD average.

- Rates of foreign objects left inside patients after surgery increased by 14% across Canada over 5 years.

Ontario’s Auditor General reported in December that nearly seven per cent of patients suffer injury in hospital. “Each year, Ontario hospitals discharge one million people,” Bonnie Lysyk said. “Of those, about 67,000 people were harmed during their hospital stay.” Ontario’s rates of patient harm are second highest in the country, after Nova Scotia.

- Hospitals didn’t always comply with required safety practices standards.

- Nurses fired for incompetence were often hired by other hospitals.

- Disciplining doctors can take years and adversely affect hospital budgets. In one instance, a hospital spent $560,000 and took several years to discipline a doctor who had “practice issues.” The same physician was also facing disciplinary actions at two other hospitals at the same time, which cost those institutions over $1 million.

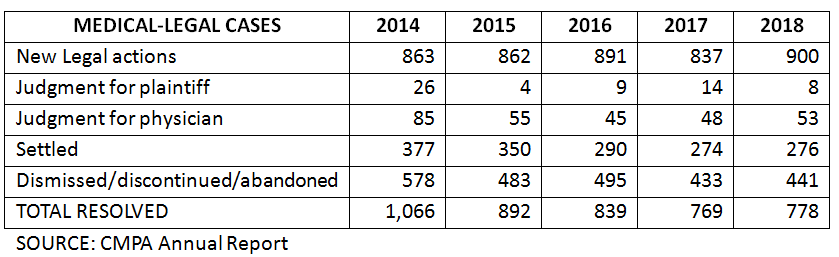

The Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA) provides liability coverage and legal support to physicians. Their latest annual report shows a general increase in new actions, but a marked decline in resolutions, indicating that cases are taking longer:

The vast majority of legal actions are in Ontario, followed by Quebec, BC and Alberta. Most actions are dismissed, discontinued or abandoned in Ontario, BC and Alberta, while in Quebec they are more likely to be settled or go to trial.

An analysis of 40 years of CMPA data shows that in the late 1970s, roughly 30% of cases that went to trial were decided in favour of the patient. In recent years, however, that figure dropped to closer to 20%, hitting only 13% in 2018.

The CMPA’s huge financial assets allow them to mount an aggressive defence that few patients can withstand. Many plaintiff lawyers hesitate to take small cases because they know how costly it can be. “Most … medical malpractice lawyers would not really look at a case that’s worth less than $250,000”, said Paul Harte, a Richmond Hill lawyer who has worked on both the defence and plaintiff sides. He believes the CMPA’s deep pockets allow them to drag out cases for years, causing many frustrated patients to give up.

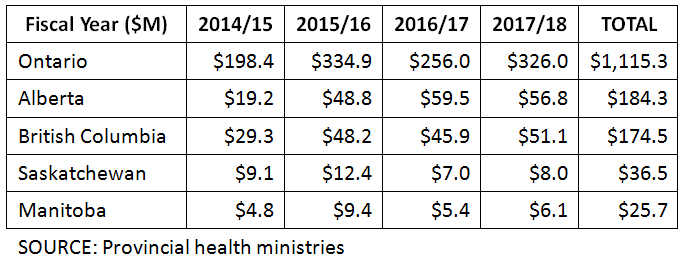

To add insult to plaintiff injury, the CMPA gets hundreds of millions of dollars every year from provincial governments. About 75 per cent of the CMPA’s funding comes from taxpayers.

Doctors do pay an annual fee to the association, but in the late 1980s – to address riding malpractice fees – the doctors’ portion was essentially capped, and the remainder paid from provincial treasuries. Today, doctors pay the fee out of pocket but are reimbursed a set amount that varies from province to province. (In some provinces or territories, this can equal the full fee).